I found this study done by the Department of Housing and Urban Development to be very intriguing….and sobering.

Being somewhat of a health and fitness enthusiast, I find that sometimes it is easy to jump to judgment, and criticism, of those who appear to be out of shape, overweight, and unhealthy. It has never occurred to me that for some folks, their daily living environment – their own home and neighborhood – could have a direct link to the state of their personal physical health.

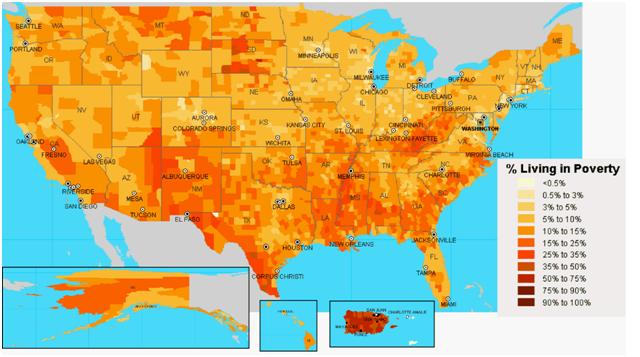

A new Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) study released last week shows fascinating findings regarding health risks for women in neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty. This is just the latest evidence proving the need for revitalizing America’s poorest neighborhoods into sustainable, mixed-income and mixed-use communities.

Having worked with MNA for the past 20 years and being part of an organization that advocates for healthy and whole living environments for all human beings, I really should have connected those dots.

Here’s to pushing for the provision of healthy homes and neighborhoods for all people, no matter what their financial circumstance may be.

The findings, which were published in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that very low-income women who are able to move from high-poverty neighborhoods into lower-poverty neighborhoods are less likely to suffer from extreme obesity or diabetes.

HUD’s Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program study tested the long-term health impacts of approximately 4,500 very low-income families living in public housing in high-poverty neighborhoods in Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York from 1994 to 1998. During that timeframe, families were randomly assigned to three separate groups: the experimental group, which allowed families to only use housing vouchers in low-poverty neighborhoods; the Sec. 8 group, which allowed families to use vouchers in any neighborhood; and the control group, which didn’t receive vouchers.

Some of the key findings featured in the New England Journal of Medicine article include:

- The women who were not offered housing vouchers through the HUD study had a prevalence rate of 18 percent for extreme obesity; the national average for women is approximately 7 percent. For the those women who received vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods, the rate was 3.4 percentage points lower than the women who didn’t receive vouchers.

- The women who were not offered housing vouchers through the HUD study had a prevalence rate of 20 percent for diabetes; the national average for women is 12 percent. For those women who received vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods, the rate was 5.2 percentage points lower than those without vouchers.

“This study proves that concentrated poverty is not only bad policy, it’s bad for your health,” said HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan in a statement. “Far too often, we can predict a family’s overall health, even their life expectancy, by knowing their ZIP code. But it’s not enough to simply move families into different neighborhoods. We must continue to look for innovative and strategic ways to connect families to the necessary supports they need to break the cycle of poverty that can quite literally make them sick.”

Sandi,

I agree – it can have an absolutely critical impact from what I’ve seen – I lived for some time amongst devastatingly poor folks in the Florida Panhandle (definitely still the South) and can tell you anecdotally that I saw this effect directly applied.

This article adds a vividness to this dimension of what we do – vital, infill communities – mixed use and dynamic, are healthier places to live with better outcomes medically, socially and academically.

Thanks for posting this – good food for thought.

– Gerard